A Simple Question

Some time ago, a colleague from my time at Lennox International, Diter Gutierrez, asked me a straightforward question:

Should All Controls from a Process FMEA be included in the control plan for that process?

There is, of course, a simple and doctrinaire answer: Yes. In fact, many supplier quality engineers use that as a test of the completeness for both the PFMEA and control plan.

However, like most simple answers, that isn’t necessarily an answer that should be accepted without question. Instead, it’s more appropriate to step back and see if that is both a practical approach, and is it a method that is effective?

If you are a supplier (rather than an end-product manufacturer like Lennox), your customer can impose any rules they want, and those rules may require all PFMEA controls to be included. As I will explain below, I don’t think that’s a smart thing to do, but the reality is that buyers can insist on any rule they want with respect to PFMEA and control plans.

PFMEA And Controls

If you use the PFMEA process correctly, you will develop a long list of both prevention and detection controls. You should have both types, not just detection (usually inspections) controls in the Control Plan. Those controls will be driven by the causes (for prevention controls) and effects (for detection controls) on the same line of the PFMEA form.

Now comes the more difficult question: which controls that are on the PFMEA should be included in the Control Plan?

There is no “right” or “wrong” answer if you want to be both effective and efficient in controlling the quality of a process.

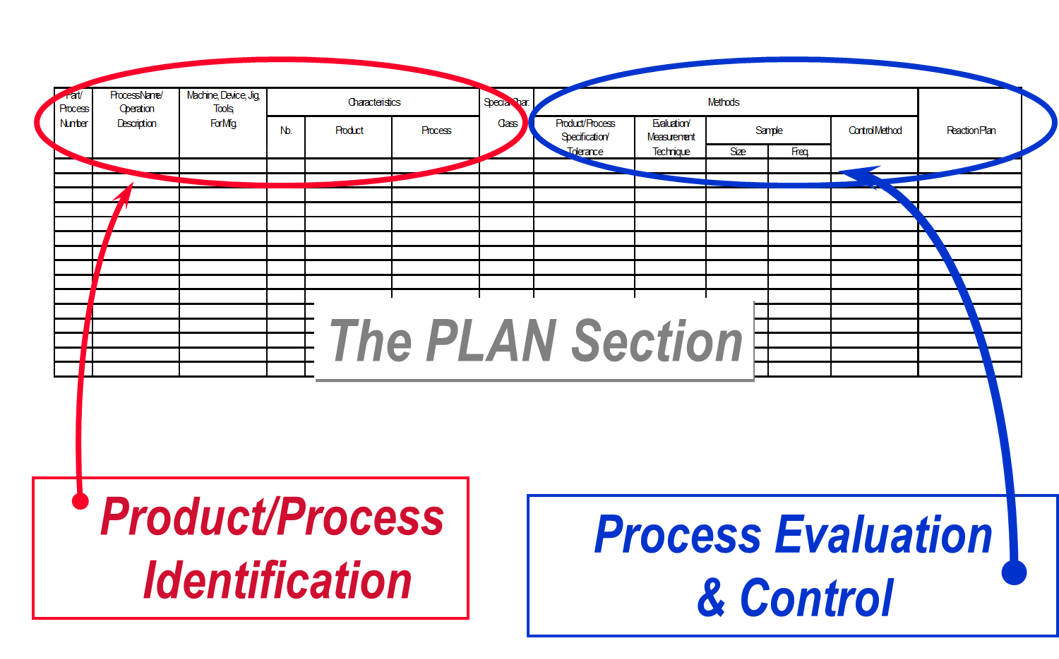

In theory (and that’s theory, NOT reality), any control on the PFMEA form should be included in the control plan. The control plan simply expands the relatively simple statement of control that is recorded on the PFMEA worksheet into an actual process control.

For example, a prevention control from the PFMEA control may say “setup check.” The control plan will then explain HOW that check should be done. Use a check sheet? Compare the setup with a standard photo of a correct setup? Get a signoff from a quality engineer or supervisor? There are many ways to do a “setup check” and the control plan will have the specific method that you want to use.

Other Considerations

However, it may not be useful or practical to include some controls that the PFMEA study suggests. There are usually three possible reasons why you might choose to NOT include a control from the PFMEA in the control plan. These include:

- The level of risk (primarily the severity but also the occurrence) is so low that it doesn’t make sense to add costs to the process to carry out the PFMEA control. (A “LOW” Action Priority Rating may be the way to look at this but that isn’t 100% correct.)

- The cost of implementing a control is too high to justify. That can be a very complex question and there is no simple test to know when it is justified but deciding that question should include senior management, at least at the factory level.

- There is some hard-to-overcome physical reason that a control cannot be done—for example, measuring flatness or cylindricity features in a part can be a very complex activity. It may be necessary to have a short process statement explaining exactly how to measure flatness. And, in that case, I can almost guarantee that any practical way to measure flatness will either be extremely time consuming OR will not really match what Geometric Dimensioning & Tolerancing means when a call out on a drawing for flatness is used. It may (and often is) difficult to get an acceptable gage repeatability and reproducibility result with measurements of these types. To paraphrase Dr. Deming, there is no real value in a measurement unless the method of measurement is carefully defined.

All three of these rationales are judgments; there are no absolute standards or rules for deciding. It may also be necessary to consider alternative methods of control, such as go-no go gaging or other techniques. Still, when all is said and done, if the net level of risk is low or the cost to do something meaningful is too high, some controls may simply not be worth the time and money—or may be impractically expensive.

However, once it has been decided NOT to include a control that is on the PFMEA in the Control Plan, then the entry on the PFMEA showing that specific control should be marked with strikethrough so that it is clear that this control will not be in the control plan. Any controls on the PFMEA that are not included in the control plan and are not marked out and explained are a red flag and deserve attention.

Once this decision is reached, the detection rating should be changed to a value that is consistent with either no controls (a rating of 10) or a reliance on the other type of control (prevention or detection) alone.

I suggest strikethrough to mark controls that will not be implemented because that will make it possible to see the original control assessment. That shows that this control was considered but not adopted. That can and should also be explained in the optimization section (the right hand portion of the PFMEA form) as well.

As long as you have a documented reason why a PFMEA control is not included in the Control Plan, that should be acceptable. Nevertheless, the reason has to make sense. It can’t just be “we don’t want to do it” or “that exceeds our targeted cost.” Those are not good answers, although the cost issue may be part of Reason #2 above in some cases.

At the end of this work, any control on the PFMEA that is NOT marked with strikethrough should be included in the control plan.

What Happens When Rules Are Enforced Without Exception?

Finally, it’s worthwhile to understand why a blanket “I want to see every control from the PFMEA on the control plan” is not a wise choice. If that’s imposed, either by management or by a customer, then the PFMEA itself will be degraded, and degradation will quite possibly be so severe that the PFMEA itself is hardly worth the effort used to conduct the study.

How will it be degraded? It’s uncomplicated. The PFMEA will be changed, manipulated, or otherwise edited to remove or modify issues that lead to an impractical control or it will be distorted to make it seem that no control is needed.

That doesn’t help anyone—not the supplier, not the buyer, and certainly not the end consumer of the final product.

Why will it be done?

Again, the answer is straightforward. If a buyer puts a supplier in a position where they will have to do something that doesn’t really stand up to reasonable and rational scrutiny, they will find a way to work around that imposed constraint. (The same is true if factory managers do this, too.)

There was an old joke in eastern Europe when Soviet style economic controls were in place. “We pretend to work and they pretend to pay us.” When the game of no-exceptions, do it our way or else rules is played in the quality arena, teams will find a way to deflect the rules.

Then that story becomes, “We pretend there are no problems and you pretend to believe us.”